Getting Ahead of the Stunt

Jan 17, 2025

Managing the Potential Corn Stunt Spiroplasma Challenge

By Joey Kuehler, GCC Sales Manager/Agronomist

Corn stunt spiroplasma disease is becoming a growing concern for Kansas growers. While it has been mostly confined to southern regions, warmer winters have allowed the disease to spread northward. Understanding how to manage this emerging challenge is key to protecting your corn crop.

Corn stunt spiroplasma disease is transmitted by the corn leafhopper. In Central and South America, where corn stunt is considered a major disease, losses can be severe. In those areas, losses can range from around 5% to 100%. Within the continental US, corn stunt disease had been limited in distribution to southern Texas, Florida, and California, as these locations more closely mimic the vector’s native Mexico environment. While it is not a new disease, it is being observed more often and in areas outside the typical locations.

While the vector does not overwinter in Kansas, warmer winters in recent years have allowed it to survive further north than it has in the past. Aided by the wind, corn leafhoppers move northward from their overwintering locations, and in the summer of 2024, both the vector and the disease were reported across Texas, Oklahoma, Missouri, and in 26 counties in Kansas. Grant and Haskell counties were among those 26, and it’s very likely the vector and disease were also present in more counties than where it was confirmed.

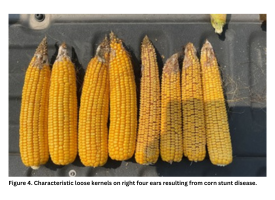

Corn leafhoppers affect corn health and yield in two ways. First, they feed on leaves by sucking plant sap. Under heavy populations, this feeding can cause dessication of those leaves. Typically, though, we just notice a shiny appearance on the leaves, as the leafhoppers excrete honeydew as they feed. This honeydew can lead to a black sooty mold growth which in turn impedes plant photosynthesis processes and negatively affects plant health. (Note that the corn leaf aphid can also secrete honeydew, so this symptom alone is not sufficient to confirm presence of the leafhopper). This direct injury is typically of only a minor significance though. During this feeding, infected leafhoppers can also transmit the CSS pathogens into corn plants, which multiplies in the vascular tissue. Symptoms of infection appear around 30 days after the initial feeding, and include general plant stunting, short internodes, leaf streaking, multiple small ears with no or poor grain fill, and leaf reddening. The earlier in the season infection occurs, the worse the damage is. What I saw this year was mostly just late season reddish/purple upper leaves, and a slightly smaller ear with lighter kernel weight. These plants only comprised a trace percentage of the total plant population, so yields were only minutely affected.

Since the pathogen is either bacterial or viral, fungicides are not effective. Additionally, thresholds for treatment of the insect vector have not been determined, and in most cases are not recommended due to the high efficiency of this insect as a pathogen vector. By the time you see the insect, disease transmission has likely already occurred. Based on some limited observations this past summer, we are advising growers to avoid a very small number of hybrids that seemed to be more adversely affected. Early planting dates also should help the crop grow beyond the most vulnerable stages before potential leafhopper activity peaks in season. Much remains to be learned about how this insect and disease impacts corn in this area should outbreaks become more frequent.

The GCC Agonomy team will be keeping an eye on your crops and watching for this as well as any other potential issues that may arise. As always, your GCC Agronomist is here to help. If you have questions about managing corn stunt spiroplasma or other crop concerns, don’t hesitate to reach out—we’re ready to work with you to protect your yield and maximize your success.